Sports Medicine researchers at the University of Iowa Carver College of Medicine are investigating how relaxin, a menstrual cycle hormone that promotes connective tissue degeneration, may be associated with joint stability, injuries, and patterns of degradation of important tissues such as the ACL and cartilage in some joints that are common in women.

Most injury prevention research is at the biomechanical level and studies the forces generated by during various movements. This tissue-level emphasis on hormone-induced changes in tissue quality could change the approach to orthopedic care for female athletes.

Fourth-year Carver College of Medicine student Emily Parker and Alex Meyer, MD, a 2022 Carver graduate, conducted the research under the supervision of Department of Orthopedics and Rehabilitation faculty members Robert Westermann, MD, and Michael Willey, MD, of the Hip Preservation Clinic. Relaxin was assessed for possible contribution to female-predominant soft tissue hip injuries. Parker and Meyer found in their scoping review of 80 studies, that unlike steroid reproductive hormones such as estrogen, relaxin is a peptide-signaling hormone triggering decreased collagen quantity and quality at receptor sites.

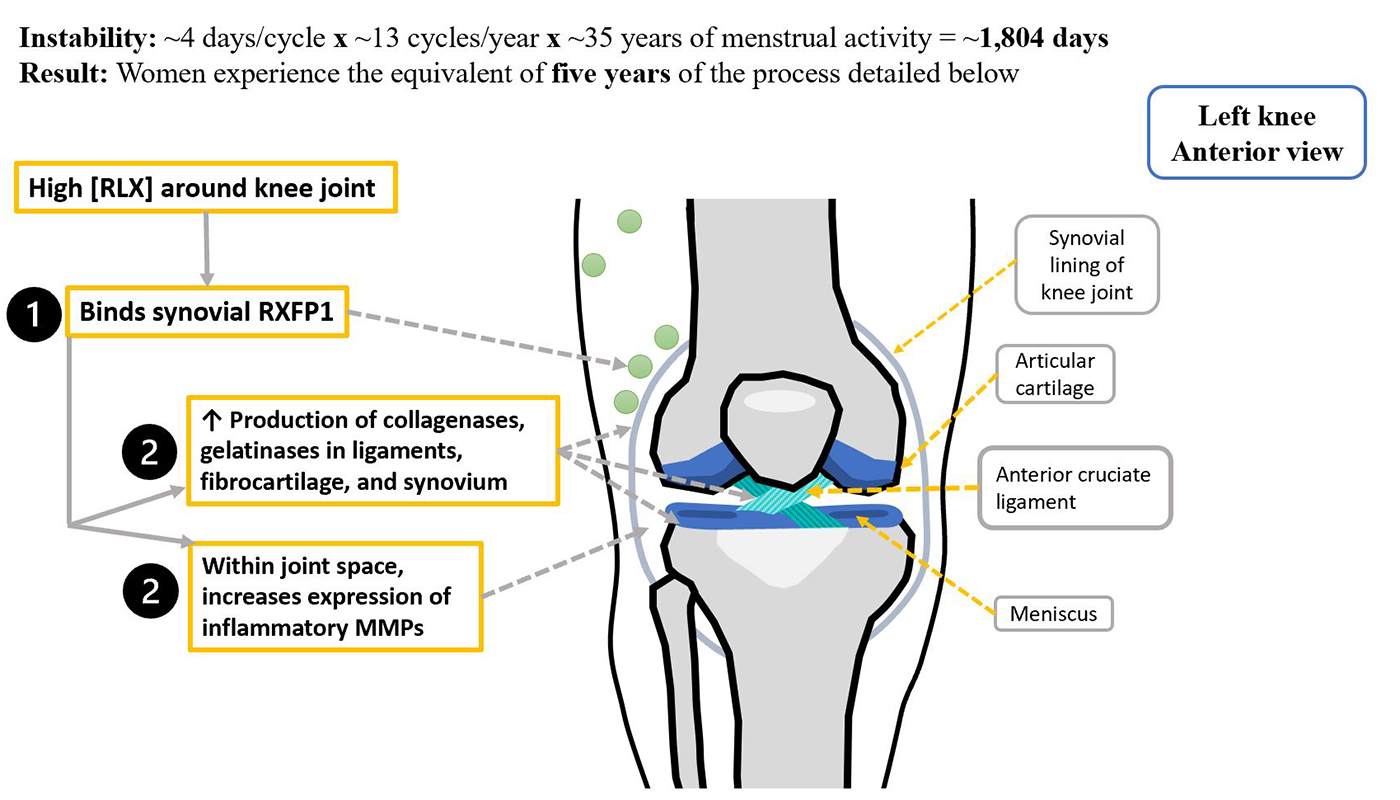

Women have relaxin receptors beyond the reproductive system, on tissues such as ligaments and tendons. These joint support structures are rich in type I collagen, which is heavily targeted for digestion by relaxin signaling. Furthermore, the receptor sites—such as the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) of the knee—are structures disproportionately injured in women.

“At certain times during the menstrual cycle, relaxin levels are high, which makes structures like the ACL and the hip labrum weak, and that may present an increased risk for females during that time,” Westermann says.

To better explore this potential connection, the research team has enlisted the expertise of Iowa OB-GYN specialists, to help understand the cyclic variation of menstrual cycle hormones and the length of the menstrual phase during which relaxin may impact joint stability. If relaxin does contribute to musculoskeletal pathology in women, multispecialty collaboration will be key for comprehensive women’s health care.

“We are working with the OB-GYN department to create a patient education handout on common, likely relaxin-related, musculoskeletal issues during pregnancy, when relaxin levels reach their peak. The handout will describe preventive strategies, symptom management, and when to consider seeing a specialist for your symptoms,” Parker says.

The two departments are also working to determine whether risk-stratification algorithms, hormone level testing, and injury prevention counseling could decrease sex-specific injury rates. Interventions such as patient education resources and contraceptive hormonal regulation are being considered for future research.

Discussing menstrual cycle influences on factors such as cyclic joint pain during a musculoskeletal health screening may seem new to many female athletes. However, Parker notes that in recent years sports medicine has begun paying greater attention to the comprehensive health of female athletes—particularly at the collegiate and professional level, where injury risk is high.

She cites increased awareness of, and screening for, the female athlete triad (amenorrhea, disordered eating, and osteoporosis) as an analogous example.

“Exercise-related amenorrhea was not discussed in sports medicine prior to its recognition as part of the female athlete triad, and a signal for significantly increased risk of bone stress injuries” Parker explains.

She hopes that sports medicine care, which accounts for unique variables of female physiology, will decrease the incidence of female-predominant injuries.

While studies are still early, Iowa researchers believe accounting for hormone-induced changes to tissue quality could help decrease the gap between rates of sports injuries in male versus female athletes.